Authors

Paul R. Buckley, Stella Bouziana, Timothy Woo, Hanna Mohamed, Aamina Ahmed, Julie Chan, Liron Barnea Slonim, Cynthia Bishop, Piers EM Patten.

Background

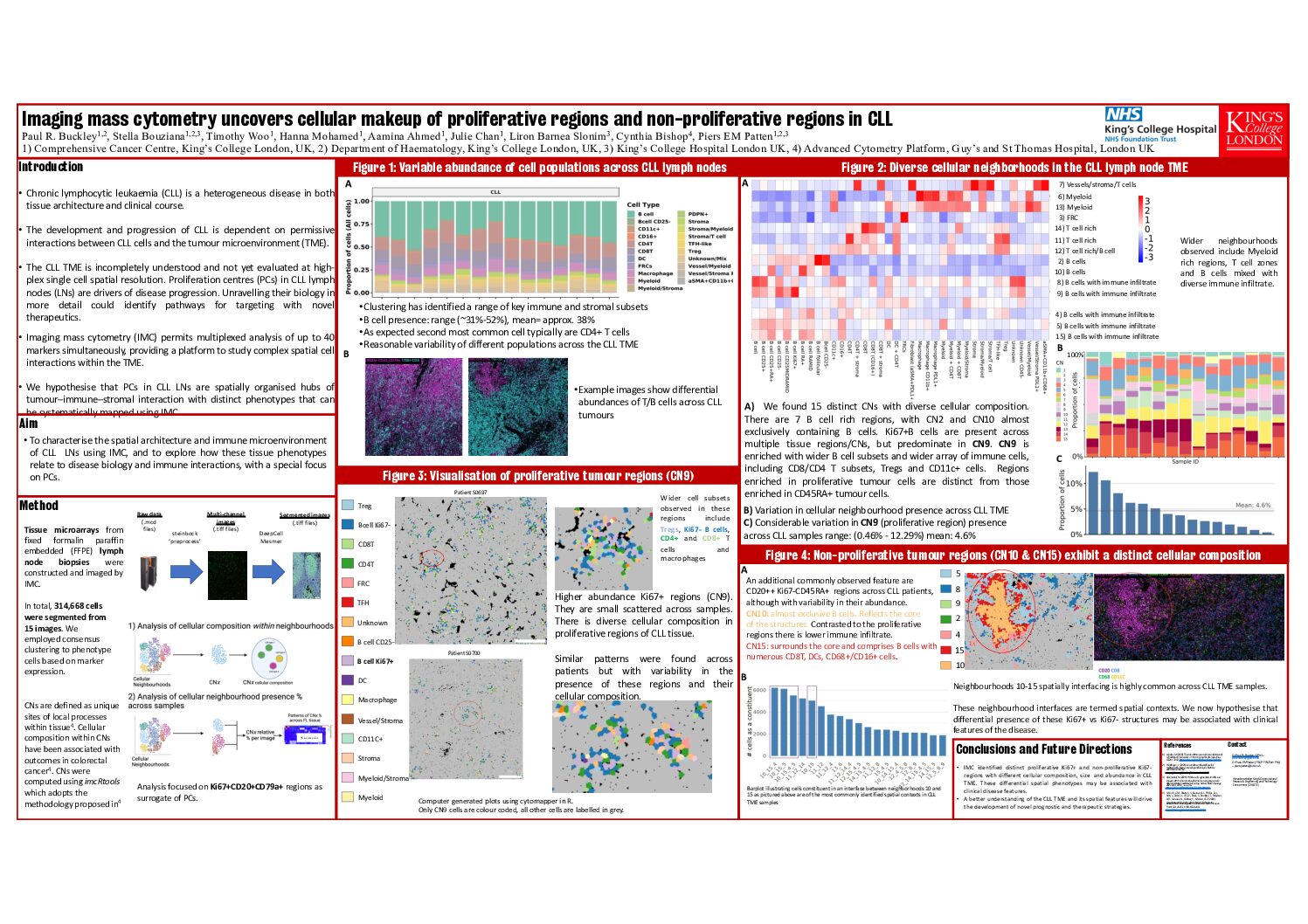

The tumour microenvironment (TME) of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) lymph nodes (LN) plays a critical role in disease biology, but its spatial organisation at the single cell level remains incompletely understood. Proliferation centres (PCs) in CLL LN, histologically defined zones enriched for larger, activated tumour cells, are considered drivers of disease progression. We hypothesised that PCs are spatially organised hubs of tumour–immune–stromal interaction that can be systematically mapped using multiplex imaging, revealing cellular phenotypes and interaction patterns not discernible by conventional histology.

Aim

To characterise the spatial architecture and immune microenvironment of CLL LNs using Imaging Mass Cytometry (IMC), with a particular focus on proliferative versus non-proliferative tumour regions.

Methods

We optimised a 31-plex panel to identify tumour, immune and stromal cells. IMC was applied to 15 regions of interest from 6 LN biopsies of untreated CLL patients. Samples were stained with metal isotype-tagged primary antibodies and imaged by Hyperion mass cytometer. The ‘steinbock’ pipeline permitted raw image pre-processing, via which DeepCell Mesmer was used for deep-learning based automated cell segmentation. In total, 314,668 cells were segmented from 15 images. We employed consensus clustering to phenotype cells based on marker expression. Post-phenotyping, cellular neighbourhood (CN) and spatial contexts were computed using imcRtools. Subsequently, we analysed i) the cellular composition within neighbourhoods and ii) cellular neighbourhood presence (%) across samples. We focused on regions enriched in Ki67+CD20+CD79a+ cells as a surrogate for PCs, reflecting their histological definition as zones enriched for larger, proliferating tumour cells.

Results

We found a heterogenous abundance of cell populations across CLL LNs with clustering identifying a range of key immune and stromal subsets. B cell presence ranged from 31% to 52% (mean 38%). The second most common population identified was CD4+ T cells. Subsequently, we characterised 15 distinct CNs, each with diverse cellular composition. Presence of CNs across CLL samples was variable. We identified 7 distinct B cell rich regions, with e.g. CN10 almost exclusively comprising B cells. Ki67+B cells were present across multiple tissue regions/CNs, but predominated in CN9. CN9 was also enriched with phenotypically diverse B cell subsets and a wider array of immune cells, including CD8/CD4 T subsets, Tregs and CD11c+ cells. There was considerable variation in CN9 presence across CLL samples (mean 4.6%, range 0.5-12.3%) which were small and scattered across samples. Intriguingly, we noted strong CD45RA+CD20+ expression throughout these tumours, finding that CD45RA+ B cells typically were distinct from Ki67+ B cells.

We next focused on the proliferative versus non-proliferative areas. A highly common feature across CLL samples were aggregates with a core strongly enriched for CD20++ Ki67-CD45RA+ cells (CN10) and a lower immune infiltrate compared to the proliferative regions. CN15 surrounded the core and comprised B cells with numerous CD8T, DCs, CD68+/CD16+ cells. Spatial context analysis revealed the most common interfacing neighborhoods across these CLL LNs involved CN10 and CN15, together forming distinct structured regions. Across samples, CN10-15 interfacing cells represented a mean ~14.17% of cells ranging from 0.91% to 37.01%.

DBSCAN was used to delineate these distinct, non-proliferative CN10-15 structures. The circularity of these regions were highly variable. On average there were ~22 structures per image (sd=14.77, range 2-49). The mean area of these structures was 5680 um2 (sd=19579 um2). Indeed, the presence, size and shape of these non-proliferative regions varied drastically across CLL tumours.

Conclusion

IMC revealed that Ki67+ vs. Ki67- tumour regions are spatially segregated and biologically distinct. These compartments differ in B cell phenotypes and surrounding immune milieu, forming functionally unique microenvironments. This spatial heterogeneity highlights the complexity of the CLL TME and offers critical insights into disease biology. Further, it provides a foundation for developing novel prognostic tools and therapeutic strategies, particularly those aimed at targeting or modulating the tissue microenvironment in CLL.

Keywords : Tumour-microenvironment, CLL, spatial

Please indicate how this research was funded. : CARP Fellowship

Please indicate the name of the funding organization.: MRC